They continue to push for seismic changes

ABOUT THIS SERIES

The Oklahoma Eagle’s “Of Greenwood” series is part of our 2nd Century Campaign, which commemorates the hundredth anniversary of this African American newspaper. This series is made possible through our partnership with Liberty Mutual Insurance.

By Gary Lee, For The Oklahoma Eagle

Photography, Basil Childers

It was one of Regina Goodwin’s first political races. “A vote for Goodwin is a good win,” was her slogan.

The campaign started mild enough, but things quickly turned fierce. So fierce that Goodwin persuaded her opponent’s campaign manager to jump ship and join her team. The opponent nonetheless won by 10 votes. Goodwin demanded a recount. In the end, she conceded. There would be other battles to fight.

Never mind that the contest took place when Goodwin was barely a teenager and a student at George Washington Carver Middle School, which was directly in her backyard off North Greenwood Avenue. The case illustrates two of her characteristics as a politician: diehard competitiveness and a tenacious will to represent the people. As an Oklahoma state representative since 2015, she has drawn from both qualities to remarkable effect.

In contrast to Goodwin, Vanessa Hall-Harper never dreamed she’d become an elected official. During her years growing up in North Tulsa, “I was the quiet one,” she recalls.

But then, after returning from four years away at Jackson State University in Mississippi, she was shocked by the dilapidation of the Northside. There was nowhere to shop for groceries. Quality housing was so scarce she ended up settling in South Tulsa. The Tulsa chapter of the Urban League and other institutions that had offered jobs and additional support to Northsiders had begun to fade.

“Something had to be done,” Hall-Harper said in an interview with the Oklahoma Eagle. “And somebody had to do it.”

She ran for City Council but lost her first bid. She was elected in 2016 and has represented the Greenwood District and much of the rest of North Tulsa ever since. She is only the second Black woman to serve on the council since trailblazing educator Dorothy DeWitty won during the council’s inaugural year in 1990. Today, Hall-Harper is the first African American woman to serve has the council’s chair.

Over the past half-decade, Goodwin and Hall-Harper have become the most prominent advocates for the Historic Greenwood District and broader Black Tulsa. Other politicians ably represent different parts or segments of the community. But the two of them are the elected representatives most Black Tulsans turn to for assistance or help with issues. In this era of Black Lives Matter and racial reckoning, they have given voice to the cries from the community for racial justice. They have also pushed for reparations for the trauma caused by the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and, in general, for North Tulsans to be treated on the same level as whites.

During the 100th centennial of the massacre in June, Hall-Harper also accomplished a first: getting the city of Tulsa finally to apologize for the massacre and destruction of Historic Greenwood. The council unanimously passed a resolution to “acknowledge, apologize, and commit to making tangible amends for the racially motivated acts of violence perpetrated against Black Tulsans in Greenwood in 1921.

“This resolution is an acknowledgement and apology and a commitment from the Tulsa City Council. It is not a reparations proposal,” Hall-Harper said in June.

“It’s about equity. The resolution is solely a vehicle to create infrastructures, or good policies that will benefit Tulsa citizens who are and who have been adversely affected from long-term systemic racism.”

What both Goodwin and Hall-Harper are most passionate about is seeking solutions to the everyday problems North Tulsans face: the lack of affordable housing, food insecurity, issues of affordable health care, and tensions surrounding policing and criminal justice.

Cherokee Meadows plea for help

Early in her tenure in office, Goodwin was marching in Tulsa’s Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Commemorative Parade when a young woman approached her and told of some seniors were facing dire housing conditions in the North Tulsa-based Cherokee Meadows senior living community near Pine Street and Peoria Avenue.

“I went over there that day,” she said. “I found people living in ‘Third World’ circumstances.” Goodwin reported the situation to federal housing officials. After three years of pressure, Cherokee Meadows owners renovated the apartments. Goodwin also helped the tenants file a lawsuit. They later reached a settlement in which residents were given financial restitution.

As a state representative, Goodwin’s reach is much broader than North Tulsa. Three years ago, she and other Democrats pushed through a hike in taxes on oil companies. During the 2018 session, the Legislature passed House Bill 1010, which increased the gross production tax on oil and gas from 2% to 5&. The increase has, in turn, led to a $282 million surplus in Oklahoma’s coffers. Goodwin believes that surplus should be used to finance social programs that help Tulsans and Oklahomans challenged by current economic conditions due to the global coronavirus pandemic.

One of the first significant issues Hall-Harper addressed was food insecurity. Incensed at the lack of a full-service grocery store in North Tulsa, she set her sights on rectifying the problem. Her first step was to push for a moratorium on the opening of discount dollar stores in District 1, on the Northside.

“I knew that the more of those stores there were in the neighborhood, the less likely it would be for a grocery store to open, and if one did open, it would be harder to have success,” Hall-Harper said.

After consistent opposition, the moratorium passed in the year 2017. And in 2021, with the support of Hall-Harper and other civic and business leaders, Oasis Fresh Market opened as the first major food store on the Northside in half a decade.

McCabe’s role before statehood

Goodwin and Hall-Harper are part of a legacy dating back well over a century of Black Tulsans and other Black Oklahomans engaging in politics.

Edward P. McCabe was one of the earliest. A settler, attorney and land agent he moved to the territory with the goal of creating a majority Black state that would be free of the white domination that was prevalent throughout the southern U.S. A New Yorker by birth, McCabe first settled in Kansas and moved to the territory in 1890.

Appointed the first Treasurer of Logan County, Oklahoma, he was one of three founders of the city of Langston. He and other Black leaders planned to use Langston to draw thousands of other Blacks to the region.

In an April 2021 article in Smithsonian magazine, Tulsa-based writer Victor Luckerson gave further details of the political engagements of Blacks in the politics of the region before statehood. A groundswell of Blacks who had settled in the territory opposed the statute whites had drawn up to make Oklahoma a state. Their primary objection was the clauses that discriminated against Blacks.

In the fall of 1907, a delegation of Black Oklahomans went to Washington, met with then-President Theodore Roosevelt, and voiced their critique. Coody J. Johnson, a Creek Freedman and entrepreneur, was a member of the delegation.

Roosevelt accepted the statehood statute anyway, racially offensive clauses and all. But the event would have lasting importance. It set the stage for the dynamic of Black political leaders of Tulsa and Oklahoman pushing the white power structure against discrimination and for the rights and respect Black Tulsans deserved.

In the summer of 1916, when Tulsa City commissioners passed an ordinance outlawing Blacks from living on white majority streets, several leading Black Wall Street business owners tried to bat it back. More than three hundred Blacks held a rally to oppose the ruling in the Dreamland Hotel on Greenwood. J.B. Stratford, owner of the Stratford hotel, then led a small group to try to get then-mayor John Simmons to drop the statute. They failed.

Shortly after that, A.J. Smitherman, editor of the Tulsa Star, the city’s leading Black newspaper, launched efforts to mobilize the political power of North Tulsans. Incensed by the local Republican party’s overwhelming support of segregation laws, he urged Black Tulsans to join the Democratic party.

In 1918, Smitherman called a meeting of Tulsa’s Colored Democratic Club. They elected top officers, including James Henri Goodwin as Treasurer. Goodwin, grandfather of current Eagle publisher James O. Goodwin, was business manager of the Tulsa Star and later a leader at the Eagle. His role in the Democratic Club marked the beginning of a tradition of Goodwin engagement in Tulsa politics that has continued until today.

In the years leading up to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Smitherman was one of the most vocal Black civic and political leaders of North Tulsa. He helped form Ward Ten, which encompassed Greenwood and much of the rest of North Tulsa and was one of the leaders of the District.

When President Woodrow Wilson visited Oklahoma in 1919, Smitherman was the only Black person given an opportunity to speak during his appearance. Smitherman’s hard push for local Blacks to vote Democrat made his engagement in a public meeting with the Republican President all the more poignant.

The race massacre came two years later, destroying much of Greenwood. It also wiped out the core of the community’s political activists. Stratford, Smitherman, and other business owners who had taken on political leadership roles were forced to leave Tulsa.

Political role played by Tulsa’s ministers

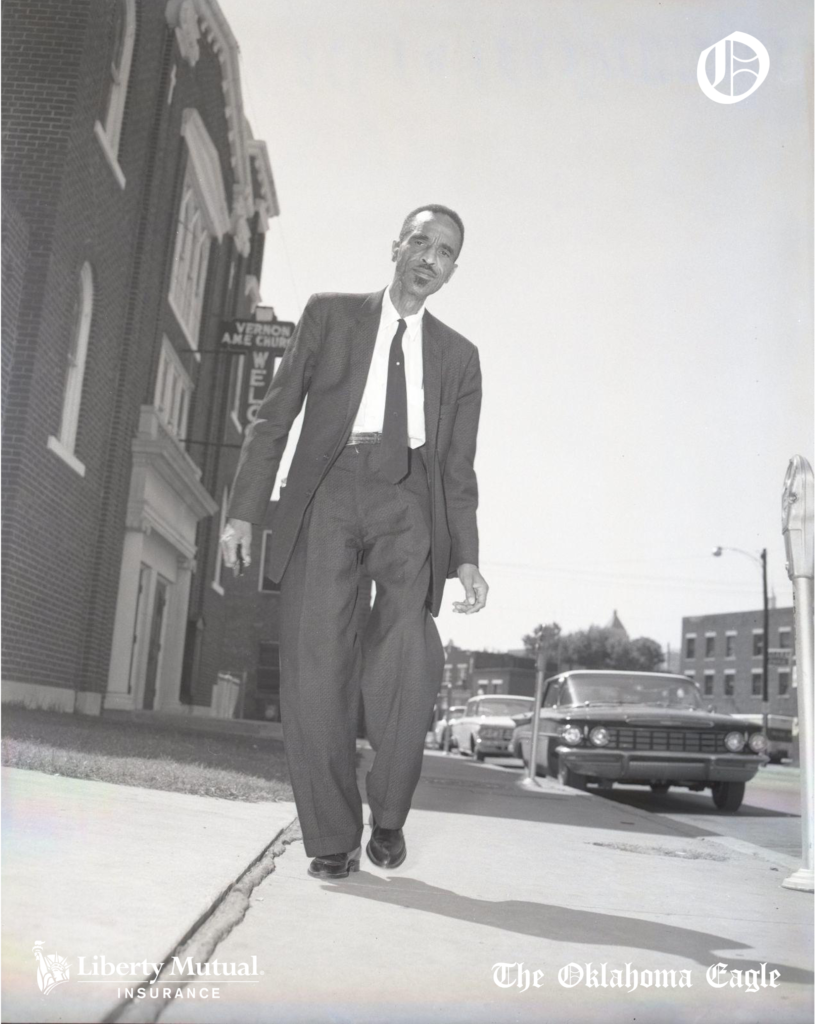

It would not be until the 1950s that North Tulsa’s political leaders would regain a high profile. The civil rights movement was calling Black leaders everywhere to the cause. One Tulsa transplant who answered was the Rev. Benjamin Harrison Hill. During a career that spanned from the 1940s to 1970s, Hill wore several hats: editorial page editor of the Eagle, leader of Vernon AME Church, and President of the local chapter of the NAACP. In 1968, Tulsa voters elected him as a state representative for the legislature. Like leaders who had come before him, his mission was to push Tulsa’s white business owners and political representatives to give Black Tulsans their due rights.

Hill collaborated with other Tulsa clergy, including whites and Blacks. His two closest pastor/colleagues were the Rev. B. S. Roberts and the Rev. Dr. G. Calvin McCutchen. The three clergymen, working with the NAACP, began organizing sit-ins. The first took place in 1958 at Katz Drugstore in Oklahoma City. In Tulsa, they targeted Borden’s Cafeteria and Piccadilly Cafeteria. By the mid-1960s, with the help of other Tulsa faith leaders, they filed a petition to create a citywide public accommodations ordinance. It passed, marking the desegregation of restaurants and other public venues.

In 1965, Hill waged another hard push for the rights of North Tulsans against the city’s power structure. He created a nonprofit called “New Day.” Its mission was to implement Tulsa’s VISTA program, designed to benefit low-income families. The effort had no support from City Hall and faced challenges getting started. The Tulsa World called it a threat to the city at large.

In response, New Day created a flyer, and VISTA workers circulated it.

“Southside Children play in beautiful parks while Negro children play in streets,” it said. “DOES CITY HALL CARE? No parks, no movies, no recreation at all.”

The ensuing public discussion led to a firestorm with city officials attacking Hill’s organization and eventually replacing him.

Curtis Lawson’s win

Curtis Lawson was another leader who answered the call for leadership in civil rights. He was a founder of the Congress for Racial Equality in Tulsa and helped organized sit-in demonstrations in Oklahoma. As an active member of the NAACP, he was a labor consultant with Rockwell International and fought against the plant’s discrimination practices.

In 1964, he was elected as a state representative, one of the first three African Americans elected to the Legislature since 1908, when A. C. Hamlin in 1908. In his four years in the legislature, one of his primary efforts was to desegregate Tulsa Public Schools.

E.L. Goodwin Sr. used the Eagle to encourage North Tulsans to use the power of the ballot. In one of many examples, a 1965 editorial criticized Black residents for not voting in local elections. “A Voteless People,” it read, “is a Hopeless People!”

Ross: ‘Pillage of Hope’

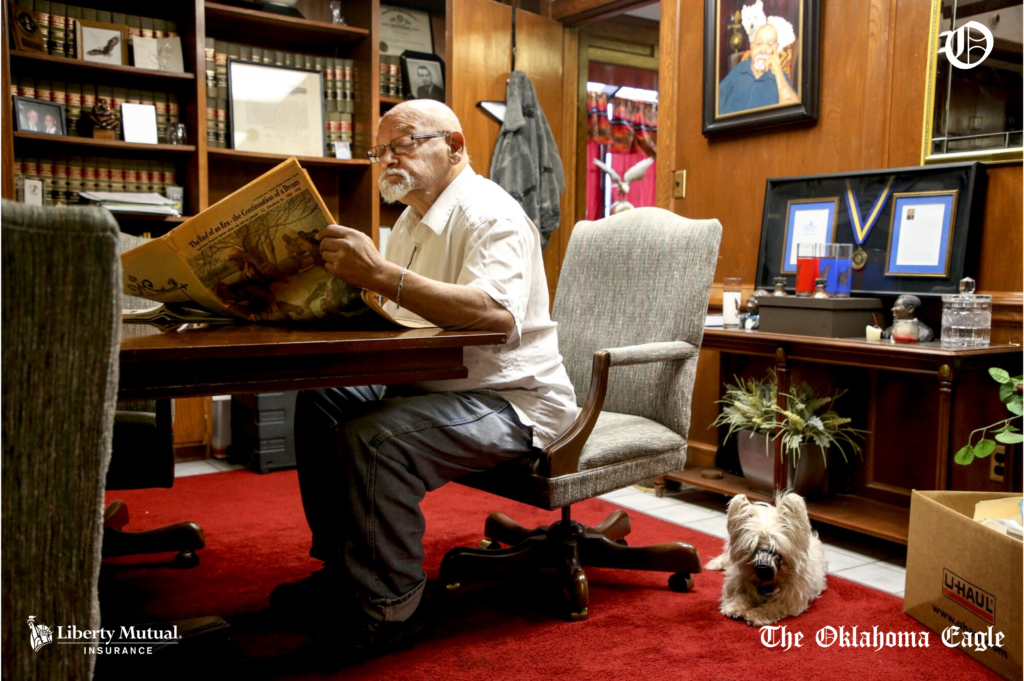

Don Ross, a prominent Eagle columnist, editor and vice president, devoted much of his writings to the dire issues facing North Tulsa. In 1982, he decided to take his activism further and run for the state legislature representing the Historic Greenwood District. He won and went on to serve for two decades. Ross’s focus was primarily on education, the arts, labor relations, economic development, and affirmative action. But Ross’s inspiration was always to improve the quality of life for Black Tulsans.

In his 2021 book “Pillage of Hope,” Ross detailed the highlights of his tenure as an elected official. Among the laws authored were Oklahoma’s first affirmative action law – a law establishing preferences for minority vendors – and affirmative action goals for higher education. He also helped to establish a state holiday honoring the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and lobbied to have Interstate 244, which runs along the border of the Historic Greenwood District, renamed for Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Of all his accomplishments in the legislature, Ross is proudest that he led the fight to take down the Confederate flag flying above state buildings. In 1989, Oklahoma became the first state to take down the Confederate flag above its governmental buildings.

Ross is credited with bringing more than $79 million to North Tulsa, including funding for health care.

Two of Ross’s projects proved to bring lasting benefits to the Northside. One was the creation of the Greenwood Cultural Center, which he consistently supported. Opened in 1995, the center is regarded as the cornerstone for preserving the culture of Black Tulsa. The other was the Race Riot Commission. He worked passionately for it to be created and for the legislation to follow through on the Commission’s recommendations.

“I wish I could report that the historical journey I have traveled has made Tulsa’s African American legacy more comforting and complete,” he wrote in Pillage of Hope. “I cannot. It remains unfinished business.”

And yet, 20 years after Ross left office, his reputation lingers. “He was funny, pointed, and very effective,” Regina Goodwin said. “Sometimes after I make a speech, someone will tell me I remind them of Don Ross. I consider that to be the highest compliment.”

Horner’s historic election

Maxine Horner, a proud product of Tulsa’s once booming Greenwood miracle, broke both the gender and color line to serve as one of the first African American women in the Oklahoma Legislature. She served 18 years as the state senator for the 11th District, including North Tulsa. She was also Democratic Caucus chair, mostly concentrating on improving education and the arts. Her tenure ended in 2005, due to term limits.

She was one of the state’s leading advocate to help struggling students get a college education and a champion of Oklahoma’s rich musical legacy and influence.

During the late 1990s, Horner worked with Ross to help create the Tulsa Race Riot Commission. When the Commission’s report was published, she advocated fervently for the wrongs wreaked on North Tulsans during the massacre to be set to right. In particular, she was a vocal proponent of reparations for the survivors of the massacre and for the descendants of victims. She and Ross authored successful legislation responding to recommendations made by the Commission. Among other things, the statute established a fund for scholarships of up to full college tuition to Tulsa students in low-income areas.

Horner also became a strong backer of the Greenwood Cultural Center and the Jazz Hall of Fame, two institutions that have been critical to maintaining the culture of Black Tulsa. Her passing last year cast a pall over all of North Tulsa.

At her passing in 2021, her children, Shari Tisdale and Don Horner Jr., said of the many lasting memories they have of their mother, they held firm to her constant reminder of service before self.

“There is one phrase from her that I keep in my wallet: ‘What are you doing today to make a difference?” he said. “That was her. I look at it all the time. It really resonates. That was her thing.”

A spirit of public service

James O. Goodwin, who has been the Eagle’s publisher since 1979, also weighed running for office. But he decided he could best serve the city’s politics running the newspaper and working as a behind-the-scenes broker. His inspiration was his father, who had been a longtime Greenwood civic leader as well as the Eagle’s Publisher.

“He strongly believed in public service and set an example for it,” Jim Goodwin said in an interview. “I have tried to follow in that spirit.”

One of Goodwin’s primary concerns was the structure of the Tulsa city government. It was a commissioner-style body in which members were elected to at-large seats. In result, Northsiders were rarely included in the governing body.

In the late 1980s, Goodwin and the local chapter of the NAACP sued the city of Tulsa, alleging discrimination against North Tulsans.

The suit drew attention to the unevenness of official North Tulsa representation in city politics. It paved the way for a recommendation that the city completely overhaul its approach to governance. In 1989, Tulsa voters passed a sweeping statute to restructure the city’s governing body. According to the new rules, different districts of the city would get exact representation on the new council.

The new structure was a boon for North Tulsa. It created District 1, which encompassed Historic Greenwood and a big swath of the Northside. That move guaranteed that Northsiders would have a representative on the council.

In turn, Tulsans in District 1 sent a series of leaders to represent them on the council.

‘I am trying to do my part’

When Hall-Harper reflects on her accomplishments as a council member, she highlights the help she has been able to give to the underserved and disadvantaged residents. One event that gives her pride is the expungement clinic she helped organize in 2018 at the 36th North Street Center. The event, organized in connection with World Won development, offered workshops on how people who have been incarcerated can clean their records to prepare to more easily secure jobs and enter society.

As Hall-Harper looks to the future, she sees tough battles ahead. But she is up for it. “I believe when we are talking about righting wrongs that government has a huge part to play,” she said. “So, I am trying to do my part.”

Goodwin also sees much work to be done. She highlighted the upcoming development in Greenwood and the battle for North Tulsans to reclaim ownership as one of the most significant issues on the horizon.

However, she added, “sometimes it’s not the big things but the smaller things that are important that people have taken their eyes off of.

Integrity matters; being principled in serving people in the right way has to matter. There is a lot that needs to be done in this city.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

“Of Greenwood,” is a monthly series of The Oklahoma Eagle that examines key legacies that helped to shape our community as the “Black Wall Street of America.” Our series receives support from Liberty Mutual Insurance. The Oklahoma Eagle is solely responsible for this content.

>> May: Tulsa’s Green Legacy and the role agriculture played in our development

>> July: The power of Greenwood’s circular dollar

>> August: The rich legacy of Tulsa’s Black entrepreneurship

>> September: Goin’ to worship: Sunday is a lifeline of Greenwood’s legacy and future

>> October: Health care: Carrying on ‘legacy of (Black) physicians’

>> November: Greenwood: A community devoted to education

>> December: Music: From Tulsa to Broadway and back

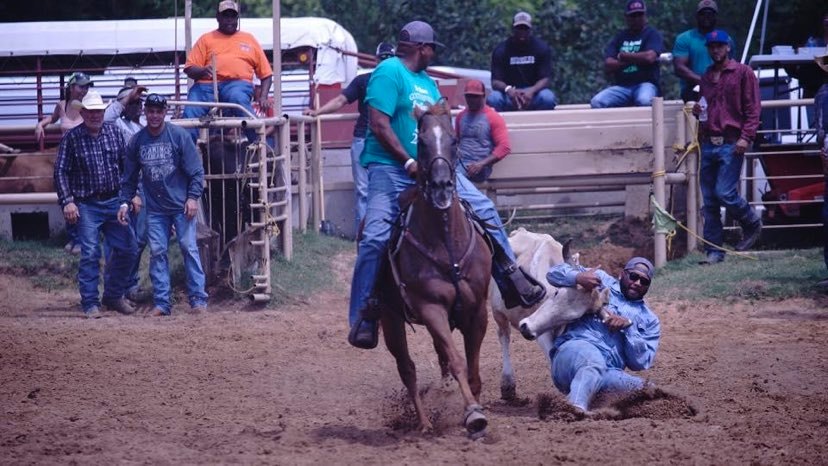

>> January: Sports: The North Tulsa Sports Machine

To read the series and watch videos, visit TheOklahomaEagle.net.