By Victor Omondi

In March 1965, Amelia Boynton Robinson led hundreds of demonstrators across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Amelia organized the march from Selma to the Alabama capital of Montgomery, along with Rev. C.T. Vivian and others. On that day, Alabama state troopers struck Amelia with a baton.

“They came from the right, the left, the front and started beating people,” Amelia told The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, in 2005. “The second time, I was hit at the base of my neck. I fell unconscious. I woke up in a hospital.”

A photograph of the incident was widely published in newspapers, and the march, which later became known as Bloody Sunday, was part of the campaign that saw President Lyndon B. Johnson sign the Voting Rights Act in the months that followed.

Civil icons like Martin Luther King, Jr. and late Georgia congressman, John Lewis, were attracted to the marches. Still, before they came into the picture, women were the driving force behind the civil rights movement from the beginning, according to Lynne Olson, author of Freedom’s Daughters.

“Men always got the attention, but the ones who were really organizing it and were really making it work were women,” said Olson. “And that was true going back to the time of the time of abolitionists.”

According to Faya Rose Touré, a fellow activist and lawyer, Amelia and her husband, who was also a voting rights advocate, moved to Selma in the 1920s, where they started their insurance business.

“They saw [voting rights] as a key to the road to justice, to equality. They saw it as the key to end Jim Crow segregation in the South,” Touré said. “They lived long enough and were smart enough to know that voting rights may not be a panacea, but it was certainly something that could be fought for.”

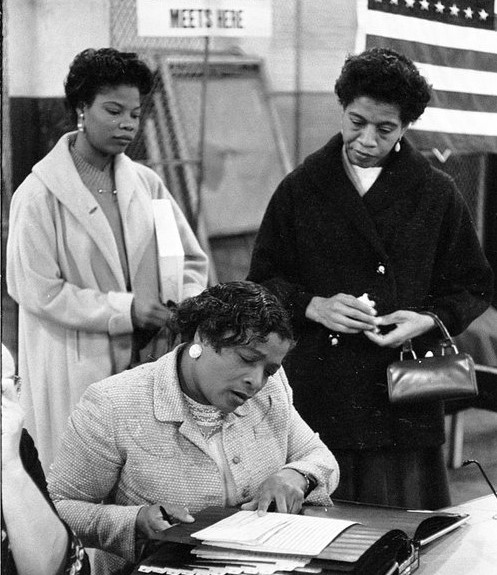

When Amelia’s husband died in 1963, she used his memorial service at Tabernacle Baptist Church as the first mass meeting for Selma’s voting rights. Marie Foster, a sister of a dentist, attended the meeting. Foster became interested in voting rights after being denied the opportunity to vote several times.

Amelia and Foster became the first two female members of the Dallas County Voters League, a group that led a voting registration campaign.