By Joy Jenkins

Nancy McDonald first met Jones, who at that time went by the nickname Clark, when he was living at the Tulsa Boys’ Home (TBH). At 13, he was quiet, shy and struggling with his schoolwork. The product of a disrupted childhood, he had never been in one home for more than two years.

But McDonald, a TBH volunteer, and Jerry Dillon, TBH executive director, saw him as a gentle soul, someone whose upbringing made expressing himself difficult. At the time, Jones was not ready for formal school, so McDonald worked with him one-on-one, reading to him and helping prepare him for the transition to a traditional classroom.

Soon Jones began to blossom. His schoolwork improved and he began playing basketball for the TBH team. A natural talent, by high school he was playing for the state champion Central High School.

A few years later, Ken Hayes, then head coach at The University of Tulsa, recruited Jones to play there. Eventually, Jones even secured a spot on a professional team in France.

Along the way, Jones had begun spending weekends and holidays with the McDonald family and, while a student at TU, moved in permanently.

More than 40 years later, McDonald remains close to Jones, as well as his son, Jason, and daughter, Sarah, who call her and her husband, Joe, “Granny” and “Grandpa.”

She recalls the day when “The Blind Side” came up in a discussion with Jason.

“It’s a lot about you and Grandpa and my dad,” he said.

And, at first glance, it is.

But Zack Jones’ story is not about just one family, although they played a crucial role. It is a story of a community of Tulsans coming together to mentor a young man whose future seemed bleak. And although decades have passed since Jones called Tulsa home, the city — and many of its residents — have left a lasting impression on him, his career and his family.

By now, Zack Jones knows that not everything in life goes according to plan. Speaking via phone from his home in Cohors, France, he recalls that his first memory of Tulsa was the Children’s Medical Center. At age 11, he was admitted to its children’s therapy program at the suggestion of a child psychologist from the state Department of Human Services. He was supposed to be there only a few weeks, but he decided he did not want to return home and stayed six months.

So Jones’ therapist at the medical center suggested another option — a local facility for boys with all types of family situations. It had a playground; gymnasium; “The Shop,” where boys could learn how to be a barber, mechanic or welder; a baseball field; basketball court; three meals a day; and a dormitory.

There was one caveat: It was 1966, the height of the civil rights movement, and he would be the first black resident ever admitted to the Tulsa Boys’ Home. Jones was unfazed.

“That’s not something that bothered me in those days,” he says. “Every day was a challenge.”

After talking with TBH Superintendent Pop Singleton and visiting the campus, Jones decided to make it his home rather than returning to Shawnee, where his mother, two brothers and two sisters lived.

Singleton was honest with Jones before admitting him to the program. It wouldn’t be easy, but if Jones were willing to make the sacrifices others had made for him to be there, he would do well. That meant following the rules and improving his schoolwork.

Many of Jones’ academic challenges were linked to his auditory learning style. As a child, he often had to sit at the back of the classroom. To avoid blame for typical classroom shenanigans such as flying spitballs, he pretended to be asleep. However, he says he heard every word his teachers said.

“I didn’t talk a lot, so when I was at the Tulsa Boys’ Home, people thought I didn’t know how to express myself,” he says.

McDonald, on the other hand, had plenty to say. Having recently moved to Tulsa with her physician husband, Joe, she was looking for ways to get involved in the community. Soon she was invited to join the Tulsa Boys’ Home Junior Association.

She remembers Dillon and Singleton announcing that the program would be welcoming its first black resident. The boy, they noted, wouldn’t talk about his past and was not ready to attend a traditional school. He needed a mentor, someone to help him open up.

They turned to McDonald and said, “See if you can get him to talk.”

“So that’s frankly what I did,” she says. “I just started reading. He was like a sponge. He just absorbed everything. He started warming up.”

To Jones, McDonald was a kindred spirit, someone who understood his challenges and embraced him anyway.

“Nancy is probably the best human being that I’ve ever met,” he says. “She has an extraordinary presence. When you’re a child and you’re in an environment that’s totally different from what you’re used to, she was there to listen to me. … I knew right away that with her I could express myself and there were no barriers.”

Many of the boys at TBH traveled home to see their families on weekends and holidays. Jones, however, chose to stay behind at TBH. But as McDonald and Jones grew closer, she began inviting him to her home on weekends, holidays and summers. It wasn’t long before Jones became a part of the McDonald family, joining Nancy, Joe and their four children, to whom Jones became a big brother.

“I just became a part of the family,” Jones says.

That family would soon have more successes to celebrate.

Jones’ basketball success is partly attributable to an Oklahoma basketball legend.

While in ninth grade at Horace Mann Junior High School, Jones attended an end-of-the-year banquet. There, he met banquet speaker Eddie Sutton, then coach of the Central High School basketball team. Earlier, Jones had played some basketball for the TBH team. Dillon recalls that Jones was still developing as a player. He could quickly run to the other end of the court, but he seemed unsure of what to do when he got there. He captured rebounds because of his above-average height, but his shooting was somewhat inconsistent.

Regardless, Jones enjoyed the game, and when Sutton told him, “You ought to go to Central. They’re going to win a state championship next year,” he immediately asked TBH staff whether he could enroll.

After the TBH team’s season ended in February of his ninth-grade year, Jones did not touch a basketball again until just weeks before Central’s season began. Even then, he was still unsure about joining the team — that is, until he met new head coach Jim Howard.

Howard, now an academic administrator for the Master of Arts in education program at St. Mary’s University of Minnesota, says he remembers when he first met Jones. He was a 6-foot, 5-inch sophomore and it was the 1968-1969 school year.

“I knew that in junior high there had been low grades, disruptive family problems and a lack of self-assurance,” Howard says. “I also knew that Clark (Zack) had started living at the Tulsa Boys’ Home and begun to turn his life around.”

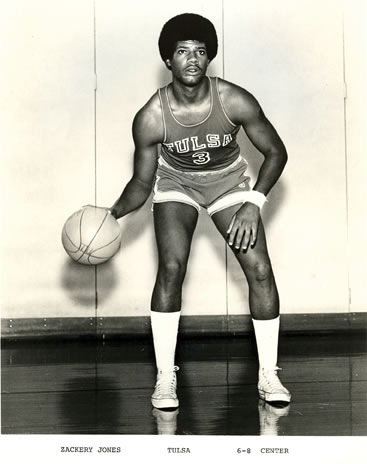

In Jones’ sophomore year, during which he played on the junior varsity team, Central won the state championship. At season’s end, all of the starting players graduated. After honing his abilities playing summer basketball, Jones stepped onto the 1969-1970 varsity team, which returned to the state tournament and advanced to the semifinals. By his senior season, the now 6-foot-8-inch Jones helped Central win the 1971 state championship.

“During that season, Clark (Zack) was described by one writer as ‘mild mannered,’” Howard says. “Another writer referred to him as ‘Superman’ for his play in the state tournament in making the all-tournament team. Both statements were accurate.”

Naturally, college recruiters had begun to take notice of Jones, and he was ready to make the transition.

Jones was familiar with The University of Tulsa even before becoming a student there. He says the university’s campus was part of his neighborhood, and he often walked by its buildings, although he wasn’t aware he was on a college campus.

Ken Hayes first met Jones during a scrimmage at Central High School. Although Jones’ team lost the game, Hayes was impressed with the young player. He remembers Jones as a “coach’s dream,” a player who never questioned what a coach wanted him to do. And although his presence was imposing to opponents, Jones stood his ground without resorting to violence.

“He was not a vocal leader, but he was a leader,” Hayes says. “He did it with actions. He had a great work ethic.”

Jones, too, has a fondness for Hayes. He remembers that prior to his joining the TU team, Hayes encouraged him to attend Crowder Junior College in Neosho, Mo., where he could prepare himself athletically and academically for the rigorous private university. During Jones’ two years at Crowder, Hayes visited him regularly and reminded him that although other colleges, including in-city rival Oral Roberts University, had come calling, he wanted Jones at Tulsa.

“He’s a guy who causes your chest to swell,” Hayes says of Jones. “He started from zero. He was very special.”

All the while, McDonald continued to support Jones, who had permanently moved in to her home. She and her family put college textbooks on tape (Jones learned more easily by listening than reading) and saved newspaper clippings about his games. When Jones learned that his given name was Zackery, rather than Clark, the McDonalds supported the change.

And when he wanted to visit his mother in Seattle one Christmas, they bought him a ticket. A few days later, he said he had seen her and was ready to come home. They made sure he got back.

Jones did not graduate from TU — he finished six hours short — and after leaving the university, he still had a desire to play basketball. He tried selling insurance, but that wasn’t filling the void. Then, one day, he picked up a basketball from the corner of his living room, twirled it on his finger and said, “You’re going to take me places, buddy.”

And it did.

After finishing his senior season at TU, Jones received some interest from the NBA and even attended a pre-draft camp with the Philadelphia 76ers. But when star players such as Dr. J and George McGinniscame on board, he realized he had to find another team if he was going to play in the NBA.

After selling insurance for nearly two years, Jones learned about a camp for a program called Athletes in Action and traveled to Colorado to try out. After a three-hour practice, he learned that the team already had a full roster, but opportunities might exist to play in France. Jones did not hesitate to say yes and moved to France for a two-month trial period. More than 30 years later, he is still there.

Now 57, Jones has only fond memories of his professional basketball career in France. Although he received offers to transfer to teams in Italy, Belgium and Switzerland, he turned them down, opting to remain with the French team.

Soon he also learned that he had a talent for coaching, and he often mentored younger players while competing for different French teams. The teams enjoyed this side of Jones’ personality because in addition to a player, they also got a coach.

“They thought, ‘We’re getting a pretty good deal,’” Jones says. “So did I.”

During his time in France, Jones, who once struggled with language, learned to speak fluent French. Now, he is also studying Italian.

France is also where Jones met his wife, Chantal, and where he welcomed his two younger children, Jason and Sarah (he also has an older daughter, Syritta, from a previous relationship).

Today, Jones continues to share his knowledge and skills with young players. Having earned his French basketball coaching degree more than 20 years ago, he has worked as a sports counselor for several city hall sports programs in French public schools.

Now coaching at the Pradines Lot Basketball Club, he has worked with players from toddler age to high school.

His children, now in their 20s, are also following in Jones’ footsteps. Both have come to their father’s homeland to pursue their educational aspirations. Having spent a summer with the McDonalds when he was 10 years old, Jason decided he wanted to finish high school and attend college in the United States. Sarah also wanted to attend a U.S. college. Both have American citizenship.

Although he lives thousands of miles away, Jones still calls McDonald, whom he calls “Mom,” and his siblings frequently, soliciting everything from the latest family news to McDonald’s advice for cooking a perfect Thanksgiving meal.

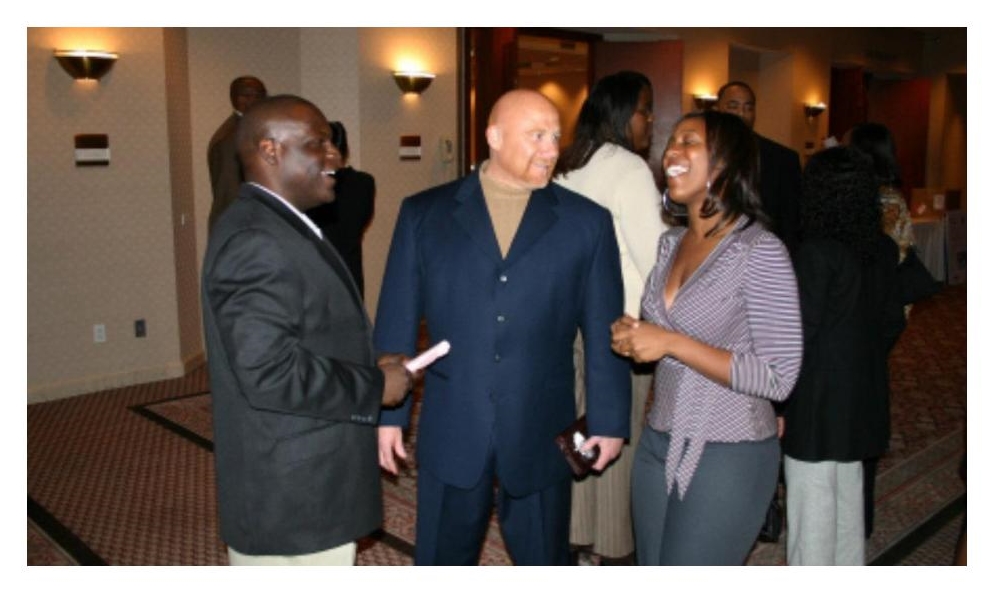

In February 2010, Jones received a homecoming of sorts. Returning to Oklahoma for Jason’s senior night at NSU, he saw not only his son but also Sarah, Syritta and his grandchildren. He also attended a gathering at the McDonald home, where he reunited with more people, including Hayes, Dillon and two high school teammates.

Looking back, Jones can hardly find an area of his life that these Tulsans have not touched. He says he often refers to Hayes’ and Howard’s coaching styles when he is working with youth, and Hayes has taken Jason to dinner to check in and provide advice.

Nancy and Joe McDonald have remained connected with Jason and Sarah and volunteered in Syritta’s daughter’s HeadStart classroom. Joe is also mentoring another young man, who will attend Booker T. Washington High School — the school his wife helped to integrate.

“If there’s a lesson here, it’s a lesson about volunteers really engaged in mentoring, and I’m talking about long-term; I’m not talking about two hours a week and forgetting them next year,” Nancy McDonald says. “That doesn’t work. If you really want to impact a child’s life, you must think of it as a long-term investment.”

His story may never be as well-known as Michael Oher’s or turned into a hit movie, but Jones is thankful that McDonald, Hayes, Dillon and others made that investment.

“I want them, whenever they think of Zack Jones, to have a good feeling in their hearts,” he says. “… They helped me to be the best I can be.”